Realize that there is a big difference between knowing the definition of a concept and having a complete understanding of that concept.

| Type of Memory | Encoding | Storage duration | Storage size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory | Sensation | Less than 5 seconds | Large (everything currently sensed) |

| Short-term | Attention | About 20 seconds | 5- 9 chunks |

| Long-term | Type 2 rehearsal | Permanent | Large |

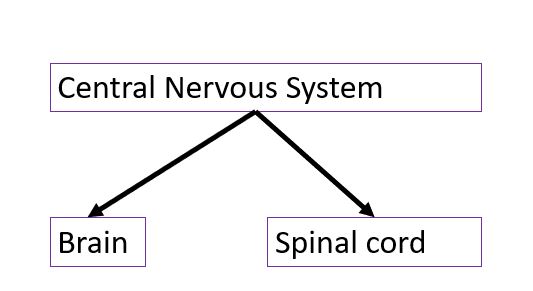

For example, if you read, "The central nervous system has two parts: the brain and the spinal cord," you might just draw something like this: