Like real banks, it is easier to make deposits into our memory banks than it is to make withdrawals (Much information is forgotten, but not gone). Below are 3 examples of retrieval--but not storage-- failures. In technical terminology, the following 3 examples illustrate that information available (stored) in memory is not always accessible (retrievable).

Because retrieval is such a big problem (and because tests ask you to take information out of memory rather than put information into memory), much of your study time should focus on retrieving--not merely recognizing!--information. Specifically, you should

Evidence that retrieval failures are not due to time alone:

| Typical Hypermnesia Experimental Procedure and Results | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Procedure | Study List of 24 Words. | Recall words | Experimenter: "Experiment is over, but would you like to come in next week for a different memory experiment?" |

"Recall words from last week." Recall 1 |

Recall 2 | Recall 3 | Recall 4 | Recall 5 | Recall 6 |

| Typical Number of Words Recalled | 18 | 3 | 6 | 11 | 14 | 18 | 24 | ||

So, on the one hand, time, by itself, does not cause retrieval failures.

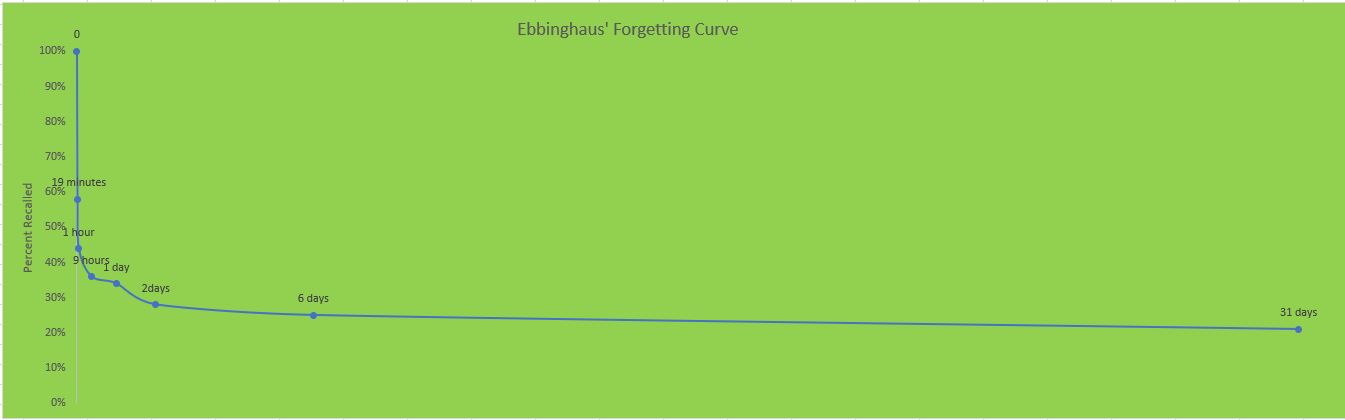

On the other hand, however, retrieval failures are often linked to time as Ebbinghaus' forgetting curve illustrates (see the graph below).

* If you just focused on the rapid drop during the first part of Ebbinghaus' forgetting curve, forgot about savings (that relearning is much faster than the original learning), and did not realize that meaningful information is retained much longer than the nonsense syllables that Ebbinghaus used in his forgetting studies, you might think that this comedian's idea for a 5-minute university was a great idea rather than just a great comedy routine.

After noting that the forgetting curve starts off as a sharply falling line, but then becomes a curve as forgetting levels off, answer the following three questions. Then, check your answers by clicking on the buttons below.

3 proposed reasons:

We will now look at each of these three explanations for retrieval failures in more depth.

Really a problem when information is perceived as similar.

So, when studying information, you should try to make the new information different from what you already know before you try to memorize it. Similarly, if you are using imagery to memorize something, you might try to make your image unusual in some way, such as making it much bigger than such normal objects really are.

2 types of interference:

Proactive interference: Old (Previously learned) information hurts retrieval of new information.

Classic experimental set up for demonstrating proactive interference:

| Group 1 | Learns List A | Learns List B | Tested on List B |

| Group 2 | Learns List B | Tested on List B |

Results: Group 1 does worse than Group 2 because proactive interference from List A acts to interfere with Group 1's recall of List B. How much worse? That will depend on how similar the two lists are-- the more similar, the worse Group 1's recall.

Think of other examples of proactive interference. Hints:

Retroactive interference: Newly (Recently) learned information acts to hurt memory for old information ("retro" means "backwards").

Classic experimental set up for demonstrating retroactive interference:

| Group 1 | Learns List A | Learns List B | Tested on List A |

| Group 2 | Learns List A | Tested on List A |

Results: Group 1 does worse than Group 2 because retroactive interference from the recently learned List B acts to interfere with Group 1's recall of List A. Will the act of learning about retroactive interference recently act to interfere with your memory of proactive interference? Have your more recent phone numbers, addresses, and passwords interfered with access to your old ones?

Animation to help you understand the difference between proactive and retroactive interference

Practice distinguishing proactive interference from retroactive interference

A phenomenon that shows both types of interference

and also shows how passing of time can't account

for

forgetting--the serial position curve:

Graph Courtesy of Creative Commons License 3.0

via Wikimedia Commons

Questions to think about when looking at the serial position curve

Given that recall is good for the beginning and for the end, but poor for the middle (e.g., we can easily remember the first U.S. President [Washington] and, despite what repression would predict, the last former President [Trump], but may have trouble remembering middle presidents like Chester Arthur), what does this mean in terms of

Your knowledge of interference can help you refute lies. The problem with trying to refute a lie is that to refute it, you usually repeat it--and repeating it may actually make people remember the lie. The solution is a "truth sandwich" in which you state the facts, refute the lie, and then state the facts again. That way, the lie is subjected to proactive interference from your first statement of the fact and retroactive interference from your final restatement of the fact. In short, just like with the serial position curve, people will remember the beginning and the end of what you said (the fact) rather than what you said in the middle (the lie).

Short (less than 1 minute) video to help you understand interference and the serial position curve.

Short (one minute) animation showing the implications of interference for how you should study.

Look at some terms that you might have trouble remembering because of interference

#2 Cue-Dependent Forgetting: Inadequate cues as a cause of retrieval failure

Cues trigger memories. In a sense, the cues you have for retrieving the information are like hooks that help you fish for information: The more hooks, the more likely it is you will catch the information. Given the importance of cues, it is not surprising that much forgetting is due to not having the right cues. Not having cues, like not having the address of a person you want to visit or not having the file name for the computer file you want to access, makes it unlikely that you will find what you need.

Examples of retrieval failures due to lack of cues:

- Often, after you say you "don't remember" something, a friend reminds you by giving you a cue ("Remember, we talked about this on Wednesday") rather than by repeating the original information.

- Similarly, you may miss a test question even though you know the information because the relevant information doesn't come to mind while you are answering the question.

- Cues are often used to help people suffering from retrograde amnesia recover their lost memories.

Implications for studying and test-taking:

- When studying, add cues to the information: If you have essay, short-answer, or fill-in tests that rely on retrieving information, you may find it almost as valuable to memorize cues that will jog your memory for the information as it is to memorize the information itself. If you use flash cards correctly or if you use the Cornell note taking system, you are probably already learning both the information and cues for the information.

Seven additional ways to remember both cues and information:

- Create acronyms. When you memorize an acronym, you memorize a cue for the words you want to remember--the first letter of those words (e.g., "HOMES" to remember the great lakes [Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, Superior], "RoyGBiv" to remember the colors of the rainbow [Red, orange, yellow, Green, Blue, indigo, violet]). So, to remember memory tips, you might create an acronym like "ETC" for Elaborative rehearsal, Testing, Chunking, or "MOST" [Make meaningful, Organize, Select, Test], or POTS [Personalize, Organize, Test, Space out your practice], or FORCE [Focus, Organize, Retrieve, Create Cues, Elaborate], or ...).

- Memorize at least one good example because examples can serve as cues. So, the more examples you connect to a concept, the more cues you will have, and thus the more likely you will be to retrieve the information. However, if you don't have many examples, one may do--especially if that example is vivid, personal, and specific.

- If, when you are testing yourself, you blank on an answer, ask yourself, "What cue can I use to recall this information if I blank on the actual test?"

- Organize material from your notes and text. You could put related concepts into groups (by putting your flash cards into piles, by making an outline, or by making a concept map) and then give each group a distinctive name. That way, you have at least two cues for the information: (1) the name you gave that category and (2) the other items in the group. Alternatively, you could integrate material from the text with your class notes or you could reorganize your class notes. Whichever organizing strategy you use will probably help: Compared to students who get low scores on tests, students who get high scores spend about 4 times as much time organizing course information.

- Put key terms on one sheet of paper. On that sheet, have four columns: one column for the term, a second column for the definition, a third column for an example, and a fourth column for a person associated with the term (for some courses, you may skip this fourth column). For each term, practice covering up all but one column and trying to recall the information in the remaining columns. Studying this way should give you three effective cues for each term: its definition, your example, and the person associated with the term.

- As you study, think of a question for which the concept you are studying would be the answer. That question will be the cue for the information. If you are good at guessing what test questions will be, you will make the actual test questions good cues for your memory.

- During your final review sessions, imagine yourself in the classroom taking the test. That way, you have given yourself a cue (the classroom) for the information that will be present when you take the test.

- When blanking on a test question, give yourself a chance to use cues by

- Looking at other questions to see if those questions cue your memory for the information.

- Leaving the question and then coming back to it. If you are not retrieving the information, the cues you are using are not taking you to the right place in your memory. Rather than continuing to use the same ineffective cues that are taking you to the wrong "address" in your memory, you are probably better off coming back to the question at which time different cues may come to mind. If it is an essay question and you are still blanking when you return to it, start writing: The act of writing may generate cues (especially if your study sessions included writing answers to questions). If you really can't think of anything to write, start writing by rephrasing the question, defining some key terms that might be relevant, or answering a related question. (Even if you don't end up recalling the relevant information, you may still get partial credit.)

- Realizing that you may have the information in a visual form, so close your eyes and try to picture a diagram, table, picture, or video related to the question.

- If you are failing to recall a word for a fill-in-the-blank type test question, go through the alphabet. The word must start with one of those 26 letters, so you will say the right word's first letter which may jog your memory for the right word.

- As you will see in the next section, because physical context is a cue, you could think back to where you were when you learned the information.

Physical context --where you were when you learned the information--is a cue that helps retrieval. How do you jog a friend's memory? Often, by talking about where they were when the event occurred. How would you jog your memory for events that occurred when you were in fourth grade? Going back or imagining going back to your fourth grade classroom would probably be helpful.

Everyone seems to know about the power of physical context except the police who have witnesses go down to the station to make a statement rather than having witnesses make their statements at the scene of the crime. (To read a one-paragraph description of the famous "jump in the lake" study demonstrating context-dependent learning in a fun way, click here)

How can you take advantage of the physical context effect to do well in school?

As we just mentioned, if you are blanking on question, it may help to think back to where you were when you learned the information. The more vividly you can mentally recreate the context, the more likely you are to cue the memory. For example, you might try to see yourself studying at your desk in your sweats, drinking from your water bottle. As we also already mentioned, you might make the classroom itself a cue by studying in the classroom or imagining being in the classroom when you study. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, realize that the more places you study certain material, the more places there are to cue that information, and the better your recall for that material should be. So, if you take your flashcards everywhere and study them everywhere, you should not have much cue-related forgetting.

Mental state can be a cue. Your emotional and physiological state--happy or sad, drunk or sober--can be a cue. In fact, your physiological state can be such a strong cue that it may seem like you only know certain things when you are in the same physiological state you were in when you learned the information, a phenomenon called state dependent learning (also called state dependent memory--but which should be called state dependent retrieval.

The evidence for state dependent retrieval is strong: State dependent retrieval has been demonstrated with alcohol, marijuana, stimulants, and barbiturates. The evidence for mood-dependent learning, on the other hand, is not strong--even though mood dependent retrieval "feels right"--what we remember when we are sad seems different from what we remember when we are happy; what we remember about someone when we are mad at them seems different from what we can remember when we are pleased with them. Because of state-dependent retrieval, you would want to be as caffeinated and happy when you study as you are when you take the exam. (If, however, you can't be as happy or as stressed during the exam as you were when you studied, don't worry: As we just mentioned, scientists lack conclusive evidence that mood dependent learning/retrieval exists, much less that it is a powerful phenomenon. )

Repression might possibly explain:

Multiple personalities, such as those described in the "Three Faces of Eve" and "Sybil" (however, the real Sybil claims her multiple personalities were faked). For a fictional but fascinating portrayal of multiple personality, watch Alfred Hitchcock's "Spellbound."

- Childhood amnesia (also called infantile amnesia): The lack of episodic memories for the first three years of life.

Problems with explaining forgetting as being due to repression:

- There is little evidence that repression is common (although we do seem to remember positive events better than negative events, and some cases like the one in this podcast suggest that repression may exist.).

- Repression is far from the only explanation for childhood amnesia. Indeed, from what you have already learned about memory, you could probably think of at least 3 other explanations for "childhood amnesia":

1. Interference: your old memories have been buried by retroactive interference from the numerous more recent events have occurred since you were an infant.

2. Cue-dependent forgetting: Even if, when you were 1 or 2, you had cues that helped you recall information, those cues were probably very different from the ones you use now. For example, although, today, asking yourself, "What did I do last Friday?" could be a useful cue for triggering memories, such a cue would have been worthless to your 11-month-old self.

3. Encoding failure: When you were 1 or 2, you often did not rehearse information, and when you did, you probably did not use elaborative rehearsal. Ineffectively rehearsed information may never have gotten into LTM.

(See additional possible explanations for childhood amnesia)

Back to Solving Encoding Problems

Copyright 2020-2023 Mark L. Mitchell